Training the Modern Workforce Live is a weekly show discussing training and talent development solutions and best practices. Hosted by Allogy CEO Colin Forward, each episode features an informative conversation with a prominent guest in the training world.

Watch the full video interview above, listen on any of the platforms below, or continue reading to see the full transcript (edited for clarity).

Click a Link Below to Listen to Episode 10 on Your Preferred Platform

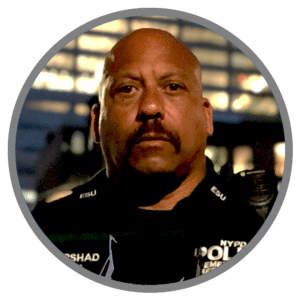

About Detective Andy Bershad, NYPD Emergency Service Unit

Detective Andy Bershad is currently in his 19th year in the New York City Police Department’s Elite Emergency Service Unit (ESU) and has over 30 years of experience in emergency medical services. Detective Bershad is one of a dozen active ESU Tactical Medical Team members, where he also serves as their team leader. Additionally, he is an active REMAC-paramedic currently practicing in New York City as well as a New York State Department of Health Bureau of EMS Certified Instructor Coordinator. Detective Bershad is also an instructor in the NYPD’s Special Operations Unit, where he teaches tactical medicine to other members of ESU and is a recognized expert in tactical law enforcement and tactical medical operations, instructing law enforcement agencies nationwide. He is a Hazardous Materials Technician and Rescue Specialist with the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Urban Search and Rescue Team, New York Task Force One and has deployed both nationally and internationally

Episode Transcript

Adam Wagner: Hello, everyone, and welcome back to Allogy’s podcast, Training the Modern Workforce Live, the weekly show discussing training and talent development solutions and best practices. Each episode, we’ll talk about a different training topic, and make sure to keep an eye out for special guests and interviews from top training professionals.

With me, as always, I have Colin Forward, CEO of Allogy. For the last decade, Colin has provided major U.S. hospitals and federal agencies with distance learning solutions. He studied mobile technology at the University of Central Florida, earning a degree in computer science and his MBA.

And joining Colin this week is Detective Andy Bershad, who is currently in his 19th year in the New York City Police Department’s Elite Emergency Service Unit and has over 30 years of experience in emergency medical services. Detective Bershad is one of a dozen active ESU Tactical Medical Team members, where he also serves as their team leader. Additionally, he is an active REMAC-paramedic currently practicing in New York City as well as a New York State Department of Health Bureau of EMS Certified Instructor Coordinator.

Detective Bershad is also an instructor in the NYPD’s Special Operations Unit, where he teaches tactical medicine to other members of ESU and is a recognized expert in tactical law enforcement and tactical medical operations, instructing law enforcement agencies nationwide. He is a Hazardous Materials Technician and Rescue Specialist with the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Urban Search and Rescue Team, New York Task Force One and has deployed both nationally and internationally.

This week, we’re going to be talking about training teamwork. We have some great questions on deck already, but feel free to ask any questions that may come up in the chat, and we’ll get to as many as we can.

Alright, Colin, over to you.

Colin Forward: Thanks, Adam. And thanks, Detective, for joining us today. It looks like we have a great audience, so I’m looking forward to getting some questions in the chat, and we’ll try and work them in as they come. So make sure to put them there and feel free to discuss what’s going on in the conversation.

Detective, you had a very long introduction because you’ve got some very impressive experience, a very diverse background, so I just want to start off by giving you the opportunity to talk a little bit about the type of training that you usually do.

Detective Bershad: Thank you. Thank you, again, for having me. So, I’m still currently active, after my long paragraph. I do enjoy doing training. I’ve been doing it for quite some time.

Right now, I run the tactical medic team. I’m blessed to be in the city of New York where we tend to get tasked with things that probably nobody would like to do. So I think one of the big highlights is preparing for it. We do a lot of sensory overload training; we create a lot of teamwork training, a lot of scenario-based training, a lot of opportunities to make you understand mentally that you can survive any situation that you might be in. I think we’ve been tasked very heavily over the years with situations that absolutely nobody anticipated coming. I think that goes on a national level, if not international.

And I’ve been blessed to have been brought forward with the gentlemen, men and women, to be prepared and listened to and to be an integral part of an instructor team—to be ready for a situation, whatever it may be, to be on hand.

How Do You Train Individuals to Work Successfully as a Team?

Colin Forward: Yeah. So today we’re talking a lot about team training. I think a lot of the time people in learning and development and people who are training professionals are focused on supporting individuals and making individuals better at performing a job. What do you think is really different about focusing on team performance and making sure that teams can perform under pressure?

Detective Bershad: I think team performance is an absolute crutch. It’s a foundation for everything that we do. Although, every person has something to contribute. I think, men and women and the trainers and operators need to know that they can operate as a team, that they can believe in each other. Everyone would like to believe that they’re amazing at everything they are, but I think we all know that we don’t really wear that cape and we’re not. And there’s a lot of support from each other.

I think the realization to know that although you’re weak in something, the person around you might be stronger with it. And I think a lot of that team building, however it’s acquired, is to know that you can rely on whoever is next to you and to know that they’re not going to surrender on you. A lot of that drive to survive and know that whatever the situation may be, that you’re going to withstand it, whatever life brings at you.

Colin Forward: So can you share some of the techniques that you use specifically to encourage those realizations or develop those skills among the teams that you’re training?

Detective Bershad: Sure. I think equipment is a lot of it—believing in your equipment before we even get to the teamwork, knowing that you can handle a task, whatever the task may be at you. The support for each other, knowing that the people around you will terminate to the end if they’re not going to survive with you.

We do a lot of sensory overload. We do a lot of, I hate to say, team building. I think a lot of the units and programs that we’re dealing with, especially my own guys within the department, have a natural reliance on the people that are next to them and supporting them. We’ll give them very off-the-wall stuff, almost bizarre stuff, with the sensory overload to know that no matter what the situation is, they can overcome it.

It might seem like a cartoonish end, but to know that they dealt with it and to know they’re pressed to task when they need to make a decision in multiple seconds that they’re able to capably clear their head and make a confident decision that will promote positively for the team, themselves, and the situation on the task at hand.

Colin Forward: That sounds really interesting. Can you provide some specifics, like give us some scenarios that you may train with teams?

Detective Bershad: We’ll do a lot of stuff where there was almost an expectation of having something simple. One simple task that we usually do when I take my medics or we’re dealing with aviation training is we’ll create a problem with just something as simple as removal. It seems easy. “Alright, I got the patient. I did great care. I’ve been a medic or an EMT, or my law enforcement officers all got in and we did a great job, but now suddenly there’s mechanical failure.” There’s an unforeseen point where other vehicles are blocking it. Alright, well now you have extended care.

And a lot of guys aren’t dealing with that. “We were supposed to get in the ambulance and go.” Well, the ambulance burst into flames. The helicopter got grounded due to weather. There are realistic points that we don’t think of that are very simple to bring into training, to give the guys the ability to be able to think on their feet and come up with a plan B. It might be that we had multiple operators or multiple people that were there that were able to do things, and suddenly we lost one or two of those people. So we went from a five-man team to a three-man team.

Well, things need to be reshuffled. I tell my students all the time, always better to die in training a thousand times than to shed a drop of blood in real-time. Know that you have the ability to think on your feet. Have the confidence to make that. We can’t constantly rely on our supervisors in a hectic situation.

Although there are supervisors and some of them are amazing, we need to support them as well, and we need to be independent thinkers and press that to the students that they know they can make a sound decision that’s going to be a positive output for the team. And they’re not locked into that decision. A lot of times I’ll vary over to decisions. We’re going to do this, and I’ll create another roadblock. Well, that plan didn’t work. I find that it’s very realistic from my years of experience in jobs. The best-laid plans go to crap in the first 15 seconds, so we need a plan B, C, and D.

Colin Forward: I can imagine that a lot of what you’re doing with emergency response and emergency medicine is about being able to respond to the situation on the fly and being able to respond to unforeseen circumstances. I’m wondering if there’s anything that you try and do to prepare people in advance of some of these scenarios or in between training. Is there any sort of sustainment that you’re doing to try and maintain this adaptability that you’re trying to imbue your students with?

Detective Bershad: I think so much of it is a mental capacity to handle any situation. I try to drill that into my students as much as I can wherever I teach. I am blessed to teach in multiple audiences. And I think just knowing or the confidence in your own self, the mental capability, that you will survive the situation, that you can depend on the person that’s next to you. It doesn’t have to be a person that you’ve worked at for years. It might be something that you’ve been tasked with for the mission that became on hand.

It might be a combination of departments or agencies that are working that are normally unexpected. And you need to have the drive to know that you will survive the situation. We find it so much with terminal patients. Being an EMS for so many years, I find that stage-four terminal diseases—once we give up mentally, we’ve given up, and you see these patients deteriorate. I’ve tried to mix that into my training with my operators and my providers, my responders, that failure is not an option.

And you need to realize that, no matter what, I will survive this situation. It may be ugly. It may not be pretty, but I will live. I will not die today. We look at 9/11-style responses or end-all scenarios that seem like they’re just, “I guess that’s it; it ends today.” No. No, because once you give up mentally, your body goes. I’ve seen so many heroic responders that refuse to acknowledge that they’ve been beaten, and you need to drive that.

And there’s nothing more powerful than your brain. The human body is an amazing vessel. Absolutely amazing and led by the brain. And having the mental capability to know that you’re going to survive this situation to any degree is mandatory. It’s absolutely, without point, critical to surviving a situation.

And I do my best to do that. I remind my students as often as I can to look around you, look at the people around you, you would lay down and die before you let somebody around you die. And we do it for a living. We do it for strangers, total strangers on a regular basis. Why would we not go higher for each other?

I think you need to realize that, and sometimes we lose sight of that. We forget. Whether it’s why we got into the business or how we maintain ourselves in the business. But to put ourselves out for a stranger, to put our lives on end is absolutely without question impressive. So I think for those in uniform around us that we treat, anything less is unacceptable. And we need to remember that mindset to go, “No matter what’s going on, I’m not going to die today. And these guys are coming for me. They will come.”

And we will. As the responders sit in the room, we all know that as we look around. We all would put ourselves in such peril to ensure that we make sure that we, as a team, as a unit, as responders, come out together. I think that’s such a critical point in surviving any mission that you might possibly be encountering.

How Does Training Help Individuals Remain in Control of Their Situation?

Colin Forward: Yeah, I think you’re raising an interesting question about the population that you’re usually dealing with, right? Because training populations are going to vary. They’re gonna have different propensities, different triggers for motivation. And what I hear you saying is that the police departments and the emergency first responders that you’re working with, a lot of the time, have an external focus of motivation knowing that someone else is depending on them. Does that ring true?

Detective Bershad: I think so. I think there’s almost an expectation, almost like a calmness, when you see a uniformed responder that comes—from whatever agency it may be. There’s an understanding of control; there’s an understanding of thought.

I love to tell my students, one of the main factors that I push through is, “I’m not shot. I’m not stabbed. I’m not having difficulty breathing.” You need to bring control to it. When we go into pediatric jobs, when we go into chaos, where we’re going into a motor vehicle accident, a fire, a tactical situation, the calmness you bring brings calm to others, not only responders but to the general public. Everything is okay now. Somebody is here that’s going to control it.

And again, I think going back to that mental thought, I think on the inside, you can kind of scream a little bit, but with good training or solid training, you know that whatever the situation that’s upon you, you can handle it. If the variance has changed, if the dynamics change, that’s okay. Stop, take a deep breath. I’m not injured.

Why Is it Important to Train for as Many Situations as Possible?

Colin Forward: Someone in the chat, it looks like Steven, said there’s a famous quote, “We don’t rise to the level of our expectations. We fall to the level of our training.” Is that something that rings true to you?

Detective Bershad: Absolutely. One hundred percent. We’re only as strong as our training. You resort back to muscle memory. I had an old sergeant teach me years ago. I’ve been blessed to have been around so many amazing people and learn and been pushed to task for situations. If you have to think about a situation, your training has failed you. If you’re pressed to task, you’re going to resort back to your training. You don’t have the time.

We all make split-second decisions on a regular basis, even in our off-duty lives, whether we’re riding an ambulance, whether we’re selling and working at a computer, we’re pressed to task. Nobody looked for an uneventful situation. Nobody looks for crises that fall in their lap. Some of us in uniform run for it. But to go back to your muscle memory, to go back and know, “This is what I do.” You’re not thinking about it.

Something as simple as tourniquets—I scream at my students all the time and I press the fact that when you apply a tourniquet, something as simple as a tourniquet, you should press that on entirely the whole way. You should have lost that distal pulse. You should be placing it on so that when, God forbid, it’s me or you or a stranger that you’re treating, you know, “No, I put it on all the away. I don’t put it on halfway because I didn’t want to hurt him. I didn’t want to leave a mark. I had to leave a note for his wife, his girlfriend, his dog, to make sure that this is why he has marks on his arm or her arm.”

No, cause you’re not even thinking about it. You’re watching your situational awareness and every time you twist that piece of equipment, it’s applied properly. And as you watch whatever else you might encounter from the job as it cascades around you, you’re prepared to deal with it. Yeah, 100 percent, I agree with that.

How Do You Train Mental Toughness but also Mental Health?

Colin Forward: So I think you’ve done a really good job of setting the stage, the environment for the type of training that you’re providing. I want to dig a little bit deeper into training tactics and some of the approaches that you take to team training. So maybe we can start with some of what you and I have talked about before about the psychological training—preparing for the impact of the event and care for the responder after the event. How is it that you deliver some of these more difficult messages to folks that are sort of a psychologically at-risk population?

Detective Bershad: Hey, again, kind of going back to the mental stability of it. We forget that we’re not Teflon. I’m sure my fellow responders will agree, we all think we wear a cape. We all think that as we tear open our shirt, the gigantic S is there, and there’s no one that can hurt us, but it’s actually not. We actually are humans.

We have amazing training, which prepares us for these situations, and to go into situations and deal with them on an almost dynamic level is crucial. As we go back to the training, I try to push them to realize that it’s okay to go home and be broken. It’s okay to watch TV or find a moment where maybe you’re watching a cartoon and suddenly you find a cascade of emotions that overcome you. That’s okay. We lose sight of the fact that we actually could have some other profession. And perhaps we were chosen, perhaps they chose us, but you’re put in a situation that’s amazing.

Colin Forward: I’m thinking training strategy here. I think those are really difficult messages to get across to a team that you’re training. I want to know what you think is most important. Is it the content of your message? Is there some way that you establish credibility with the audience that you’re training to? Is it a matter of making it participatory? How do you establish credibility with these audiences when you’re trying to get across some of these difficult messages?

Detective Bershad: I need them to believe in themselves, and I think that’s, as instructors, something that we need to instill into them: knowing that they have the power. “Well, I work in a little department. Well, I never had this situation before.” No, you can handle it. Rely on your training. And again, rely on your capabilities.

Rely on the team around you. Where you may fall short on something, someone around you is going to pick up that pace. The performance of a team is what does it. We are individuals, but we operate amazingly as a team. When we look at the group effort and knowing that whatever the situation may be, however dire it may be, that you’re able to overcome it.

And it might not be you that contributes, but we all contribute. I’m blessed to be in such an amazing department and unit and run through situations that have gone through. But the teamwork and the capabilities of those around me—who might be unsung, it might be unexpected—we didn’t know that he would do that. Maybe it was great training at some point. Maybe it’s the belief in yourself that there’s nothing more powerful than yourself to drive through. We look at heroics and it has nothing to do with heroics. It has to do with confidence, training, and believing and wanting to complete a situation for the best outcome for each other, for the best outcome for you.

We deal with death, disparity, injury on a regular basis, and anything to any one of us in uniform or our fellow coworkers in whatever arena you may be in is unacceptable. And we put ourselves out, and we need to instill in these students and each other that is an unacceptable outcome.

The risk that can outweigh a situation sometimes, it’s better to slow down. By slowing down, that tenth of a second where we’re asked to make life-and-death decisions in a hundredth of a second. It takes a hundredth of a second to blink. So imagine trying to decide, “Should I shoot? Should I run in and grab them? Should I jump out the window? Should I try to make an escape in a different direction? Is someone in trouble?” Alright, a hundredth of a second, as quick as it is to blink, you’re forced to make that. And I think that if you instill that confidence in yourself to know that you can make that or buy that extra hundredth of a second or two to three seconds can seem like 20 minutes to make a safe decision.

Colin Forward: Okay. So I understand wanting to communicate to your audience that they need to have confidence in themselves, right? But then, there’s also this need as a trainer, as someone who is responsible for this audience, to probably help them understand why you’re the right person to deliver the message, right? So, we had someone— it looks like Marty in the chat— say, “One way to do this is by leading from the front and not from behind a desk.” So what do you think that looks like to you?

Detective Bershad: I’m going to have to agree again. A leader doesn’t necessarily have to be in a supervisor role. I think we follow the strong personalities, and a leader will show by example. He won’t hide. He won’t promote. He’s going to go in and put himself in that situation, along with the people that believe in him or her. Where are they putting themselves out? I would never ask any of my officers, my coworkers, to any degree to do something that I wouldn’t do.

And I think that creates a respect and a trust. The press to task in a situation is going to be overwhelmingly supportive. I think that’s a critical point to understand and to go with that. To direct from behind and to put people in life-and-death situations from almost a command position can create almost animosity.

It’s a necessary evil. I’m not putting down any upper executives. If there’s anyone in this room, I apologize. I don’t want it to come across that way. But I think there’s a control that needs to be done on the mission and the job that’s a necessary evil. But when we look at our boots-on-the-ground guys, we look to each other and we know, I can run through fire with this guy or gal.

Whatever happens, I know they’re going to be by my side. There’s an old saying that I like to go with when I try to instill it with myself, and maybe something to put to your students, “Stand next to me and you’ll never stand alone. I will never leave your side.” And I think that’s a comfort that we need to put with our students and with our coworkers to know, “Listen, no matter how bad this gets, everything is going to be okay because we’re doing this together.”

Colin Forward: So I have to ask, this training that you’re talking about, I have to imagine that some of the folks that are a lot of times sitting behind a desk are participating in this training too, right?

Detective Bershad: Oh, a hundred percent.

Colin Forward: And so, is it the same message to them, or do you think there’s a little bit of a different curriculum that goes into making sure that everyone’s prepared if they’re called on to be extraordinary?

Detective Bershad: I think everyone should be prepared for a situation. Just the fact that you sit behind a desk, the fact that maybe you’re in a different role, doesn’t change the fact that you might end up in a situation. A mission, an event, will not start discriminating, “Oh, wait a minute. You normally do this. Let me not bother you.”

We might end up in something in our personal lives. We might go into a grocery store to stop and get some items for home and find yourself in a situation that was absolutely unintended. That doesn’t mean that we should be any less prepared for it.

There’s so much of it is training and to instill that would carry you through life. And on a day-to-day operation, where we pass off things to our co-workers, to our children, to other strangers who may not be in the business. “Well, I’m a landscaper. I do this. I would never run into shots fired. I would never pick up somebody who’s bloody. That’s disgusting.” Well, you might find yourself in that situation unknowingly.

Colin Forward: Yeah, that one hits pretty close to home. I’m here in Denver right now. It’s been that kind of week for us.

Detective Bershad: I’m terribly sorry about your loss. That was an amazing job done by all. And I’m sorry that you have to deal with that. Thank you, Colin.

Colin Forward: Yeah, I haven’t had to do much, luckily, but it seems like the Boulder Police Department handled it very well. And more to your point that there were a lot of folks that were in that grocery store on a Monday, and just like you’re saying, it’s good to be prepared.

What Is Flying Aces Consulting, and How Do You Train Preparedness?

I do want to shift gears a little bit because we haven’t talked about Flying Aces Consulting, and I know that’s a little bit different than what you’ve been talking about with the police department work that you’ve been doing. So can you tell us a little bit about that? And then, I’m going to dig into the type of curriculum that you’re developing.

Detective Bershad: Sure. So Flying Aces is my own personal company. We concentrate on tactical training as well as situational survival—a lot of what I’ve been doing over my 35-year career and 27 years with the police department. We try to create exactly what we’re talking about, that confidence in going to a situation. I’ve done a lot of executive protection training.

We continue to do that with the medical aspect of it—of again, knowing you can survive this situation. We end up with principles and sometimes their families to “Well, I have the children of a rich guy, or I have my client, I just have the wife of the family.” But threats are everywhere.

Again, going back to the grocery store, going back to that—being prepared, having a couple of items. I drive around with a tourniquet in my truck, right in the door. I do a class for a gun shop that’s out here where I deal with a lot of first-time shooters, a lot of understanding of medical awareness, just having the right tools to be prepared for it. One of the things, just to break off from Flying Aces, was the 23rd-street terrorist job that we did in Lower Manhattan. What I found that was amazing, how I talked about pushed to task, was the number of people that stepped up.

If you’re unfamiliar with the job, it was Halloween. There was a terrorist that rented a Home Depot truck and essentially drove down the bike paths of Lower Manhattan. Obviously, his goal was to kill as many people as he could. He was remotely successful. But the response back that I found as we went through the carnage and the crime scene and tried to save people and secure the area was the number of people that stepped up.

That’s you guys. That’s us. Just because you’re a nurse, just because you’re a doctor, just because you’re a police officer, a fireman—you have the ability to help. Are you leaving yourself the tools? You already have the knowledge. And as we look for the tools, the kits that came out that was included my Pathfinder truck, or maybe I keep a little bag, bleeding control, an oh-crap kit to be able to make a difference in some simple tasks. Even the confidence of psychological first aid. “Hey, listen, I’m right next to you. More help is going to be here in a minute. But I’m okay.”

We look at so many people that when we lose a loved one or a family member, “Well, I hope they didn’t suffer. I hope they didn’t have a problem. I hope it wasn’t an issue.” We look for that comfort. Isn’t that kind of our role? And I try to instill that in my students as we go through. That gentle touch, that gentle kindness that pushes it through.

Colin Forward: I want to dig into how you do that. So let’s zoom out a little bit and look at the whole training timeline. A lot of times what we deal with at Allogy is ramping someone up to in-person training and making sure that they’re getting more out of that face-to-face time, providing that just-in-time training so that they have something to reference after the fact and so the skills are staying fresh, and sometimes, augmenting in-person training and providing some additional resource that makes it more engaging. Tell me about your training timeline. What does it look for someone who’s going through training with Detective Bershad, leading up to the training, during, and after?

Detective Bershad: I try to build self-confidence in the students that are there. I’m blessed to have a very busy career. We look at hybrid programs and different things. I get some complaints from students that complain about the death by PowerPoint. It is a necessary evil. We need to get point factors in. I do a lot of things for the NAMT with my company, with Flying Aces as well as going through. But yeah, you know what, a lot of that legwork is fine to be pushed to get a lot of that general, and then to finish it off or top it off or clean it up with an instructor, preferably with some experience.

It doesn’t necessarily have to be me. Listen, there’s always somebody stronger, faster, better. But to put somebody up with an understanding, again, to build back in that confidence that you have. “Well, I just sat through a bunch of stuff on the computer, and it seemed interesting.” And I think you need that hands-on to clean it up. There’s a lot of street tricks and things that we learned through experience that aren’t going to be taught in a lecture or a PowerPoint.

Colin Forward: We’re never going to really replace the value of face-to-face learning, right? But we have found that people are more likely to retain what they learn face-to-face if they have that before and after. So is there anything that you feel is really important for someone to have on hand after one of these trainings to make sure that things stick and that they’re able to perform at a high level?

Detective Bershad: I try to build them into confidence again, from the teamwork to having the equipment to being prepared for a situation, knowing—again, back to that mental point—that there is nothing that you can’t handle. If I go into a situation and there are burning babies falling out of the sky, stop, take that deep breath, understand, “You know what? I can deal with this. It’s going to be okay. Cause right now I’m not hurt. And I have a tremendous situation on hand. And what is the best way to break it down?” Don’t try to take on a situation or mission as a whole. Once you start slicing it up, almost like eating a piece of food, but you’re not going to eat it in one big bite.

Colin Forward: So I guess another way to ask this is: how often do you think a lot of these messages about preparedness, resilience, and teamwork need to be revisited?

Detective Bershad: I think it’s something that often needs to be revisited. I don’t know that there’s a value of too much. I coordinate with a lot of my students just the understanding of liaising with other departments. You might be an EMS department that works next door to a police department, but if I’ve never seen your face, it’s human nature to not have that comfortableness, like “I’ve never seen this guy before in my life.” Think about if you go to a party, totally away from a large event or mission. If I go to a party, and I see Colin, like, “Oh, I remember Colin. He and I met him once five years ago, but I don’t know anybody else here.”

There’s going to be almost a comfort zone or a relaxation. “Let me go nuzzle up next to Colin because at least I know him because I don’t know anybody better.” The first time you’re getting pressed to task should not be the first time you’ve seen some of these faces. It shouldn’t be the first time that you’re training.

There should be coordinated training with each other. The aspect of understanding the other person’s duties. If I’m in law enforcement, EMS, or fire, I should have an understanding of my responsibilities. We’re so quick to judge, like “Well, why didn’t you do this? And why didn’t you do that?” In training, we can cover that. “Wow, is that what you guys have to deal with? I had no idea.” When now I’m taking law enforcement and I’m putting them in an EMS role going, “Holy cow, that’s what you have to deal with to keep this guy alive.” And I think it puts a different perspective or spin.

Why Is Interagency Training and Communication so Important?

Colin Forward: How much of your training is interagency? How much of that cross-pollination are you getting between EMS, police departments, different groups?

Detective Bershad: It varies from department to department and different agencies around the country, I’ve found. I’m blessed with the NYPD; they’re very good about interagency training. Sometimes it’s just that olive branch to put out.

I do a lot of different agencies and it’s, “We don’t deal with PD, or we don’t deal with EMS. We don’t deal with fire.” That’s not helping anybody. Put that olive branch out and get a comfortable zone so when we’re pressed to task, a rescue task force, suddenly a large active shooter event or even a large motor vehicle accident or fire, there’s almost that comfortable zone that comes through and the beginning of that teamwork that’s so crucial to handle any event that’s coming through.

Colin Forward: I’m curious about managing those different cultures. So do you feel like the curriculum or the training delivery needs to change to accommodate those different audiences—say, police departments versus EMS?

Detective Bershad: I don’t know that the curriculum has to change as much as the values and the drive of the goals that you want me to change. If there’s a standoff between departments or agencies, or it could even be companies or departments within your own agency, at some point, somebody has to give.

Somebody has to come in and like, “Listen, I brought some pizza and some chocolate cake, and we’re going to sit down, and we’re going to iron this out.” And much nicer to do it on that level than when bullets are flying or tragedy is upon us. We’re getting pressed to task. Have that comfortability. You should understand each other’s equipment.

“We went out and we bought this really cool equipment.”

“Well, I’ve never seen that before.

“It’s very simple. Let me give you an idea how to do it.” If I ask you to retrieve a piece of equipment for me, I might not have the understanding to work it, but don’t I create another set of hands to be able to do it?

If I understand your policy, if I’m setting up a casualty collection point, or this is our standard operating procedure, but yet, 10 feet away, somebody else’s standard operating procedure’s entirely different.

Colin Forward: That seems like a difficult thing for you as a trainer to be able to keep up with if you’re training external agencies. So I guess, being at NYPD, you’re probably pretty familiar with the equipment or familiar with the agencies that you work with, but is that something that you have to work into training when you’re, say, working as Flying Aces, working with external groups where you may not necessarily be as familiar with the equipment or the environment that they’re in.

Detective Bershad: One hundred percent. And I think that has to come from the internal group that’s there. It’s something that I push with my company as well as the department to have an idea, even within our own department. We have such a multitude of units with different equipment that is going through. Have you seen it before?

I always try to activate or push through that sense of urgency—with Flying Aces, what I’m doing—to understand, put out, again, put out that olive branch, invite them. It doesn’t have to be for a training curriculum. How about we just sit down and talk? What are some of the capabilities we have? Tabletop exercises. Make people realize, “You know what, if we have a situation, we’re probably going to be in some trouble here if we don’t correct this.” Knowing that we reach out. Contacts. Training. Merging our equipment as we move forward. Equipment is expensive. Lifesaving equipment is. I’m okay with that. I like surviving missions. I think most of us do.

But having an understanding, knowing to retrieve it, knowing their capabilities. Do I have to go three towns to get an armored vehicle? Do I have to go 20 minutes to get a technical rescue team? Do I have the capability of medical care right at the scene within my own department or within my reach that’s able to do? And that’s only left open by communications.

Colin Forward: I could imagine that’s probably a conversation that is maybe a bit more open in an interagency setting. I’m curious now because we’ve talked about the guys that are behind the desk versus the folks that are on the front lines. So do you generally have a mix of people within a department when you’re training that are, say, higher and lower ranks, and do you have to navigate those sort of departmental politics where, say, someone who’s more senior may not necessarily be as up to speed on the newest equipment that they’re using on the front lines?

Detective Bershad: I think like anything else, in-service is so crucial. It falls down on the responder, and it’s their responsibility. There is an expectation. Again, my unit is very intense on that. And something that we push as instructors, and I would suggest other instructors do too, is just because you hold a rank, whether it’s the less likelihood of you being involved, not only to know your capabilities but to have a general understanding of the equipment as a mission or an event becomes larger.

You may be pulled to task. We kind of go back to that, “Well, I sit behind a desk; I don’t do that.” That’s unacceptable. There’s an expected role for you to go through. And I think that comes down a lot to the provider as well, to whatever rank they may be. To have an understanding, to know, and to watch your men, men and women—so much of the teamwork, we look at the end-all event. “Well, this one was shot. This one that fell.” We recently in our local area just lost a heroic fireman in a pretty bad fire. What was the appointment there? How were the people around you? Everything doesn’t have to be that end-all. We spoke before about leading by example, leading by the team. You don’t need to be in a position of rank to take on a leadership role.

Colin Forward: I’m just trying to relate to what I’m familiar with, and I’m not as experienced with the way that PDs train. We just started working with LAPD, but I’m much more familiar with the Defense Health Agency that we work with at Allogy, where they have a process where it’s very learn, do, teach. And so, I’m wondering, as an external trainer, are you often working with these folks in-service that are training down the line, maybe they went through this training last year and they’re now helping you or participating in some way, taking on more leadership responsibilities within their department.

Detective Bershad: Absolutely. I think you find that even through training, you find people with leadership capabilities that didn’t realize they had them. None of us want to come to the front and be like, “Listen, I’m in charge. I’m great. That’s why I’m going to take over the role.” We find a lot of our unsung heroes that come through—that consistent training with being tested, putting to task.

I love pulling my supervisors out of the line. “This one got shot. This one got hurt.” There was a two-prong or three-prong attack where we lost our supervisor. Now, we’re being pressed to task. And where do we turn back to? Back toward training. In-service is critical. Yes, you can’t be a scuba diver and, “Well, I got certified 15 years ago,” and suddenly you’re expected to suit up and go into a high current area to go perform a rescue without some confidence in the equipment that you using, without confidence in your skills.

Colin Forward: So do you have a standard curriculum for the type of in-service training that you’re doing, or is it different from department to department?

Detective Bershad: I think it’s different departments. I think you need to adjust to the area that you’re in. It’s kinda hard to base off of us. I’m a 35,000 man department. I do a lot of programs with my company that could be 200 men, 300 men and women. Some as little as 30 and 40. We get a lot of standoff people that want to come in and just better themselves. I love that. I love when rescues want to better than themselves.

There are times that our departments provide money for training and equipment. But sometimes, if you invest a little bit in yourself, it might be something to save yourself or those around you.

Colin Forward: So, for example, it looks like Darren in the audience mentioned being a chief from a volunteer fire department in Oklahoma. So how do you have to adjust for the type of training you’re delivering at NYPD versus someone at Darren’s scale?

Detective Bershad: I think it’s just adjusting to the situation that you have. If you have a small department, is it really a difference? Don’t get that false sense of comfort. “Well, nothing will happen here. This is just Oklahoma.” You have a responsibility as a chief. If you’re pulled back, bring some of your people up. Find your stronger people to bring them up, to encourage them into a leadership role, to have them have that confidence. If I’m left to make a decision, I’m comfortable with it, knowing the equipment, knowing the capabilities of the chief.

There could be a lot to task if you’re operating through. I remember a large explosion, a terrorist attack many years ago in Oklahoma. “That’ll never happen here.” I worked with many people, and some of them didn’t come home the day of 9/11. “What are the odds they fly a plane into the tower? Come on, that’ll never happen.”

Colin Forward: To that point, we work with a lot of groups like, say, smaller hospitals where they may not have the training resources on hand. And one of the things that we try and do as a business is provide them with on-demand training so that it’s a bit more asynchronous—they’re not depending on having access to in-service training. So do you see a need or value in the type of training that you’re doing for point-of-need training for just-in-time resources?

Detective Bershad: I think it’s a marriage; I think it’s a happy marriage. To have downtime and to go over points, and we talked about the lecture points—almost like tabletop exercises. When we go through, it’s not an actual event, but it sparks our mind to think of it. “Wow. I forgot about that. I haven’t heard that in a while. I need to think about that.” You’ll hear me reiterate situational awareness on a constant basis, but as we go out and we’re the boots on the ground level, or even on a leadership level. “What happened? You just lost two or three of your men and women. Did that dynamically change it? What would you do?” It’s constantly revisiting—not to a 24-hour period. None of us actually wear that cape for 24 hours, seven days a week.

We have lives. We need to realize that the job that we have, as important and critical as it is, it’s just only a piece of our life. But we don’t practice to be dads. We don’t practice to be homeowners. We don’t practice to mow the lawn. But you know what? We need to practice and stay abreast of situations that could leave us in a situation that could leave us or someone around us severely injured.

Should Individuals Seek Out Their Own Supplemental Training?

Colin Forward: Yeah. So, Selwyn in our audience said, “You can’t always depend on your organization or department for training, it’s incumbent on the individual to seek out training courses to further your skill set.” What kind of training do you encourage the folks that do go through your programs to seek out on their own time?

Detective Bershad: I absolutely encourage the training out of your own pocket. Sometimes it can be frustrating, but I don’t know if anyone here in the room can put a price on their life. If we’re getting the TV at home, would we want the cheap-style TV, or do we want something nicer? Thinking about spending a few dollars for better equipment to put through in a situation where you’re tasked.

I love scenario-based training, and something I would put forth to the Oklahoma chief: maybe you don’t have the budget to have mannequins, but you have people. You have community groups, companies, Cub Scouts, Girl Scouts, Boy Scouts that can be victims and create situations that you can’t create. That might not be something that you find at work. To find something where you getting experienced people from whatever level they’re at to instill some of these street situations. As much as we’re taking from that PowerPoint or that ongoing constant training, we always want to be pressed harder.

We always want to raise the bar. And I think that’s so crucial. Some of the things that we do: IEDs, explosives. We’re blessed, and thank God for our men and women in uniform operating overseas. One day, sadly, it may be here. Are you prepared to deal with it?

Do you think about it? Do you have an understanding of explosive devices? How would you react? Bombing injuries, explosive injuries that you might deal with. These are the things that you’re probably not going to deal with it on a regular basis that you might need to go to an isolated program.

We do a lot of counter-terrorism events, FEMA classes, events to prepare you for situations that you may think that you may never enter. And if you take one or two things from them, didn’t you win the game? If you carry a lot of things in your car, then when you sell it, move it, break it, you take a lot of stuff out. But the one time you need it, you’re like, “Man, thank God I had that crazy triangle flare box that lights up. That might’ve saved my life. I’m so glad I had it.” Right?

Colin Forward: Or that tourniquet, right?

Yeah. So we’re coming towards the end of our time here. So I want to let everyone in the audience know that if they have any questions to get them in now. But while we’re giving folks a minute to do that, I want to ask you, Detective, what do you think are the biggest opportunities in the training space for people in these critical jobs, frontline jobs? What do you see as the biggest gap in the type of training that people are generally getting delivered and the biggest opportunities for improvement in the type of training that we’re investing in?

Detective Bershad: I think the best thing that I would like to see is adapting to the situation that you’re in. I could never compare the New York City Police Department to the Oklahoma Fire Department. A lot of the equipment, we’re blessed to have the access, the budget, to some training, to some equipment that might be there. But know your resources, know the capabilities that you’re having.

It doesn’t make you any less capable to realize that. Again, going back to that mental structure, and so much that I try to push in other instructors that I teach and students that I get, take a step back, take a deep breath. How do I slice this up and deal with this situation? Instill that into your supervisors, into your line leaders. Instill that into your students as you’re going through.

What can I do? How do I get to the finish line? “Well, I don’t have this cool armored vehicle, or I don’t have 4,000 guys to do.” Well, that’s not going to change in the situation. So how do I reach the finish line? What are some of my opportunities? How can I think outside the box, create that independent thinking, that’s not going to terminate the situation but contribute to de-escalating it? And I think that’s tremendous in any region that you’re in.

Colin Forward: Other than hiring Flying Aces to help communicate this to their department, is there something that you think that the people can inject into their training or a type of training that people maybe need to keep on their radar and pay closer attention to so that they are delivering those outcomes?

Detective Bershad: I think there’s always the source of outgoing training. Of course, I would love everyone to come to Flying Aces. But don’t be afraid to listen to the outsiders. I’m probably the third largest army in the world with the police department that I’m affiliated with, but we’re not beyond listening to others. Don’t think that you know everything. Don’t be afraid to listen to the guy in the four-man department who might have an idea. Don’t be afraid to listen to that rookie, to the new guy, to the new copy girl, to the new provider that might actually have a good idea. As great as we think it’s working, there may be something better.

Don’t be afraid to move forward. Don’t be that guy that we’ve done this for 45 years, and this is why we do it. This is 2021. We get set in our ways. We’re comfortable with it. It’s worked, but with the equipment around us, with the dynamics around us, it might be time to modify and go.

Leave your ears open. Don’t be afraid to listen to outside sources. Your own students might be giving you an idea. What’s best for the team? What creates a safe environment or safety through the mission or the event that we’re going through? That’s going to be the best outcome for everyone. Bring in outside thoughts—different points in different regions.

I’m going to bring a different perspective to Oklahoma. Oklahoma is going to bring a different perspective to Florida or California, right? “Ooh, we didn’t think of that.” But we can twist that into, “Well, we don’t have the mountains, but we’ve got a lot of planes here,” and we can kind of twist that to work for us or make it safer for us, our providers, and our rescuers.

Colin Forward: Yeah, I think it was a great point, and that’s definitely something that we encourage too, whether we’re working with care teams in hospitals, the military, or businesses. I think it’s always really important to get those different perspectives and make sure that everyone gets a chance to be an author, gets a chance to be a trainer. And that’s, I think, a great perspective to end on.

I want to thank you for your time today. You obviously have a lot of fans in the audience. There have been some people saying some very nice things about you. So I hope you got a chance to read some of the comments.

I certainly enjoyed getting your perspective. Thank you for everything that you do for NYPD and for keeping the rest of us safe. And thank you for joining us today and appreciate everyone for tuning in.

Detective Bershad: Thank you all so much. Colin, thanks for your time. I appreciate it. I look forward to seeing you all soon. You all be safe out there, please.

Adam Wagner: Yeah, thanks, everyone. This was Training the Modern Workforce Live, presented by Allogy. If you’d like to explore previous episodes, subscribe to our YouTube channel or like us on LinkedIn and Facebook. And if you’d like to connect with one of our learning specialists to see how Allogy could help improve your training, head to allogy.com and schedule a demo.